Monday, December 15, 2014

Ebola demands our full attention

The cheery and

intelligent man who operates our local dry cleaning agency and I often chat. He

has a son doing medicine, and last week, he was worried about Ebola.

He feared that casual

contact in his shop or, in the case of his son, on the wards might lead to the

disease.

It made me realise

that it is easy to overestimate community understanding of the basic facts

about Ebola.

Not that as health

professionals we know all there is to know about it - even the precise details

of its transmission are uncertain - but sharing what we do know can help the

public manage its anxiety.

And quality vigilance

depends on good intelligence. So what do we know? The first good thing - and

there are not many - is that over half the people who contract it recover.

It is less certain how

recovery occurs and whether classic principles of immunity apply, but a 50%

recovery rate is a lot better than we saw with HIV in the early years.

Medical care also

helps. Fluid replacement and intensive care make a difference to survival

chances.

Second, the disease

thus far appears to spread through blood, sweat and other body fluids,

especially the excreta of infected people, to those who touch them during life

or death. Airborne transmission has not been documented.

In theory, this means

that enhanced infection control procedures can protect family and health

professionals.

However, as of the end

of October, about 500 healthcare workers had contracted Ebola and half of them

had died, so protection as practised at present is far from perfect.

Third, we live in an

age of brilliant technological possibility, so the search for a drug to treat

Ebola or a vaccine to prevent it is likely to yield dividends quickly.

The most likely

limits, with so few cases, will be political and economic, as the cost of

developing a drug or vaccine may not be a good commercial deal. But the

accolades that would come to the inventor of a drug or vaccine would be great.

Furthermore,

technological fixes are not always expensive. As reported in the 27 October

issue of the New Yorker, a recent competition run by Columbia University

yielded several inexpensive innovations designed to assist in managing Ebola.

The competition,

auspiced by the schools of public health, and engineering and applied sciences,

was open to all students and faculty. Among them was an inexpensive hose that

sprayed bleach foam rather than a solution, because unlike a bleach solution,

with foam you can see where it has been sprayed.

But there are

significant endemic barriers to combating the virus in West Africa.

The impoverishment of

the countries where Ebola has become an epidemic is a major limitation, both in

the treatment of those with the disease and the control of its spread.

Poverty means fewer

healthcare facilities and medical supplies, which is why the military support

offered by the US, with its sophisticated logistic capability, will make a huge

contribution.

Last month, 4000 US

troops with cargo planes stuffed with all necessary equipment and transport were

deployed to Monrovia in Liberia as part of Operation United Assistance.

With that as a

background, groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières and other NGOs' efforts

will be enhanced by field hospitals and supply lines for IV fluids and material

needed to care for Ebola patients.

Medical volunteers

from Australia are also contributing to the Ebola effort - including

supporting diagnostic laboratories that are hard-pressed to keep up in the

affected countries, and are working with MSF and the Red Cross on the front

line.

This month, the

Federal Government pledged $20 million in funds for the private healthcare

company Aspen Medical to operate a 100-bed hospital in Sierra Leone that will

be run by 240 healthcare staff, some of whom will be Australian.

The move came after

weeks of public accusations by the AMA and NGOs that the government was not

doing enough.

However, until

effective treatment and infection control measures are more widely implemented

in Africa, the course of the epidemic is hard to predict.

I understand that the

mutagenic potential of the Ebola virus is no match for influenza, but if its

mode of transmission does expand to include airborne routes, the challenge of

the epidemic would grow enormously.

Figures published by

the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say almost 5000 people in

West Africa have died from the virus, with the number of cases in Sierra Leone

and Liberia said to be doubling every 20 days, which means that by year's end,

those affected will be approaching 1.4 million.

It is clear Ebola

deserves our serious attention: just as we view the extremist Islamic State as

a distant threat to Australian security, so too we should view

Ebola.

As for my friend the

dry cleaner, when he asked if he should wash his hands after handling

unfamiliar garments, my cautious (but not entirely rational) answer was, yes.

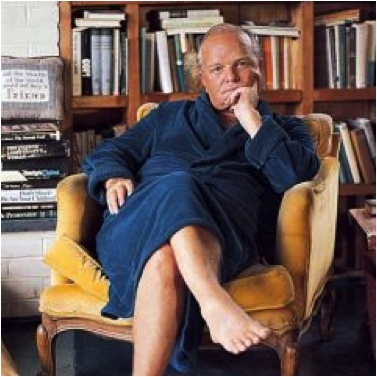

Professor Leeder is a member of the Menzies

Centre for Health Policy at the University of Sydney, chair of the Western

Sydney Local Health District Board and editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal

of Australia.

Published in Australian Doctor 17 November, 2014 http://bit.ly/16p4FTz

Stronger focus on drug side effects needed

Randomised controlled

trials are the supreme method for determining whether a new treatment,

frequently a new pharmaceutical, is superior to current best practice.

They were originally

used in agriculture to assess the added value of a new plant or soil additive,

but are now firmly ingrained in medical practice.

I recall 30 years ago,

an eminent professor of surgery railing against randomised controlled trials,

which he considered utterly inappropriate to determine the value of surgical

interventions.

He wrote a scathing

article in which he referred repeatedly and disparagingly to such trials as

"agricultural statistics".

While the randomised

controlled trial has given us the best possible evidence about the effects of

new therapies for a range of conditions, especially cancer and cardiovascular

disease, and have underpinned the evidence-based medicine movement, they do not

cover the entire treatment waterfront. This is especially so in relation to

side effects.

The way randomised

controlled trials work is that they aim to find out how many patients need to

be treated — either with the new therapy or the old — to determine if the new

drug is better.

The expected

improvement in cancer trials is small, usually less than 10%, and so these

studies require larger numbers of patients to be sure that even the slightest

difference in outcome can be seen.

Sample size

calculations, therefore, are based on the detection of relatively rare events,

such as a gain in life expectancy or quality of life.

But side effects are

another matter. They often fall beyond the vision of the trial, or out of focus

of its carefully calculated sample size.

Side effects may not

occur for months or years after a trial has finished, or they may be so rare

that the randomised controlled trial's sample size is insufficient to detect

them, even if they occur during the trial.

With some medications,

side effects are of huge importance — for example, if the trial is testing a

preventive intervention such as immunisation, rather than a treatment for a

serious illness where side effects may be tolerated.

Nobody wants to enter

a trial feeling whole and well and leave it with a nasty side effect.

Publicity around

claims of side effects from immunisation illustrate this point, and show how

critical it is to be secure about the proposed preventive interventions.

Similar concerns

surround trials of cholesterol-lowering drugs in very low-risk populations.

Side effects can be hard to detect, and if the treated trial subjects are at

low risk of the disease (such as an MI) that the drug is intended to reduce but

then develop problems with, for example, muscle power, a hard-to-resolve

problem arises. Witness the controversy around the Catalyst TV programs

on exactly this topic.

So there is a sizeable

challenge to be sure that we know what side effects occur, and brilliant

randomised controlled trials will not necessarily tell us about rare and

distant ones.

Currently, especially

in the case of new drugs, the pharmaceutical company sponsoring the trial will

have given serious thought to this matter and have in place systems to collect

information about side effects.

Of course, it is not

only in the context of randomised controlled trials that side effects occur and

old remedies, especially in specific genetic subsets of the population, may

cause rare problems. Often more information, especially long-term data, is

needed.

An intelligence system

to learn about possible side effects is far more feasible today than even 10

years ago.

The high degree of

electronic connectivity that we all enjoy (and sometimes loathe) can put us in

touch with agencies, such as the TGA, to report possible side effects at the

click of a mouse.

Now the TGA has come

up with an online reporting system for patients as it's concerned that the vast majority of

side effects go unreported. Doctors report some and drug companies others, but

for over-the-counter and alternative medicines, there have been no formal

reporting pathways.

The TGA may easily be

overwhelmed with side effect noise and it will need a good filtering system to

detect the signals. But this is surely a move in the right direction; another

step to ensure medication safety as well as efficacy as we continue to advance

our capacity to prevent and to treat.

Professor Leeder is a member of the Menzies

Centre for Health Policy at the University of Sydney, chair of the Western

Sydney Local Health District Board and editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal of Australia.

Published in Australian Doctor 8 October 2014 http://bit.ly/1BRzk91Monday, September 22, 2014

How should we respond to the Ebola virus threat?

We Australians live in an exceptionally safe country compared

with many others today (and compared with our own in times gone by) when it

comes to serious infectious diseases.

Our immunisation programs have succeeded brilliantly against

whooping cough, polio and the other diseases of childhood.

The basics of public health -- clean water and waste disposal --

are secure in urban and much of rural Australia. Huge gains in life expectancy

have followed.

We no longer need the rituals and beliefs to comfort us as did

families in Victorian England when the death of children from infections was

commonplace. We are not a society facing the loss of 16 million deaths of

combatants and civilians as happened in World War I, followed by about 50

million more who lost their lives from the larger scourge of H1N1 influenza in

1918.

Being unaccustomed to catastrophe, especially those due to

infections, it is understandable that we are shocked and frightened by the

current outbreak of Ebola virus in West Africa.

Well, even if we aren't ourselves, then at least a friend of

mine is. This man, a retired, successful and highly intelligent businessman

living in the north-east of the US, recently cancelled his summer holiday in

the south of France.

You can read about the fascinating history and virology of Ebola on

Wikipedia. The virus was named after the river in the Democratic Republic of

the Congo (then Zaire) where it was first isolated in 1976. The current

outbreak in West Africa is the first recorded for that area.

On 8 August, the WHO declared the outbreak to be an

international public health emergency.

As of 21 August, the WHO reported there had been 2473 cases of

Ebola virus in places such as Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, and

1350 people had died from the disease.

Infectious agents can kill in epidemics by being highly lethal

and highly contagious. Highly lethal infections that are not contagious do not

create epidemics.

Viruses that spread by airborne droplets such as influenza are

highly contagious, but many forms of flu are benign because their pathogenicity

is low.

It is only when a strain of influenza that has high lethality

and is highly contagious -- such as the H1N1 influenza that followed World War

I -- is circulating abroad that serious flu epidemics occur.

In the case of Ebola, there is high lethality associated with

human infection. About half of the reported cases see the patient die due to

massive cytokine disruptions to the vascular tree. But bodily contact, or

contact with bodily fluids, is necessary for infection.

The Ebola virus does not mutate rapidly -- it's 100 times slower

than influenza A and about the same as hepatitis B. If we could develop a

vaccine, it would not be quickly out-of-date.

So what should we, in Australia, do? First, we need to ensure

our surveillance strategies are sound and in place, concentrating especially on

plane arrivals of people from West Africa.

Second, we need quarantined treatment facilities available to

effectively manage cases.

Two US medical attendants, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, who

were exposed to Ebola while treating patients in Liberia were repatriated by

air on 2 August to a special facility at Emory Hospital in Atlanta, built with

the Centers for Disease Control. The US is thus taking seriously the

possibility of treating patients with Ebola on its shores. So should we.

Third, we should, as a nation, contribute what we can to the

advancement of scientific understanding of this threat, with an eye on

antiviral therapy and vaccine development.

Australia's response has been appropriate to date, but we still

do not have a national centre for disease control.

The surveillance networks that we have are generally adequate,

but relatively informal and for a nation of our wealth, aspiring to

international leadership, 'adequate' is not the word that comes to mind as an

expression of appropriate ambition or responsiveness.

Professor

Leeder is a member of the Menzies Centre for Health Policy at the University of

Sydney, chair of the Western Sydney Local Health District Board, and

editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal of

Australia.

Published in Australian Doctor 26 July 2014 http://bit.ly/ZEx5FW

Thursday, September 11, 2014

WHY CO-PAYMENTS ARE NOT ALL GOOD

In

celebrating the one-year survival of the Abbott government former prime

minister John Howard was reported to have asked why, if we have co-payments on

pharmaceuticals, we should not have one on general practice. Five reasons stand

out.

First,

the co-pays on prescription drugs stop poorer people from accessing to them.

Ask general practitioners. Extending co-pays to general practice compounds

rather than solves this problem.

Second,

seeing a doctor for a health worry is different to filling a script. A

consultation with a doctor may dissipate the worry without further cost or

action.

Third,

a timely, uninhibited consultation for the first symptom – chest pain, let’s

say – of a serious problem may save a life and nip the progress of a disabling

illness. Co-payments diminish easy access for less affluent Australians to

general practice

Fourth,

a consultation may lead to preventive changes – quitting smoking, behaviour

modification, stopping unnecessary medications – that are positive investments,

not sunk costs. Co-pays that inhibit

preventive consultations diminish the chance of a healthy life.

Fifth,

many general practitioners in poorer parts of the country who entirely

bulk-bill do not have the financial systems to raise fees. The logistics of collecting and remitting a

co-payment could drive them out of business.

Maybe

the co-pays on pharmaceuticals are a public policy error that permits gouging

of pharmaceutical prices and diminishes the search for efficiency in drug

supply. Rather than asking where else we can impose a co-payment, the question

should be, “We don’t have co-payments on general practitioner bulk-billed

consultations, so why should we have them on prescribed pharmaceuticals?’

By

way of postscript, the current debate about how much the Medicare levy

contributes to health care costs is informed by figures from the federal

minister that are all wrong.

ASSESSING VALUE BEFORE DEMOLISHING

In the current confusion in health that has followed from a

swath of defunding, abolitions, co-payments and diminished Commonwealth funding,

it is easy to lose sight of the needs of the individual patient.

Typically and increasingly, the people who need our health care

have a combination of problems such as diabetes and heart disease requiring concerted

attention from hospitals, community nurses, general practitioners and

community-based specialists. We do not have the firm evidence to say how best

to do this, and hence in NSW the state minister for health, Jillian Skinner,

has allocated $130m over 3 years to test out alternate ways of achieving this

end. Recently Medibank Private and other

private insurers have expressed interest in testing strategies using community

nurses to achieve the best alignment of care for our typical patient.

One of the casualties of the federal slashing has been what

was called a Medicare Local, an organisation established by the previous government

to create an environment of support for general practitioners and the long-term

care of patients with chronic problems.

Their function was patchy, as expected from new entities, but where they

worked they worked well. But the decision was taken recently to scrap all 61

and start again, with different, fewer entities called primary health

networks. Demolition and rebuilding is

an expensive hobby.

In NSW, where we have 17 hospital districts or networks,

there were 16 Medicare Locals. While the

match was imperfect, you get the drift.

In places such as western Sydney, fortune favoured us and the Medicare

Local and the hospital district covered the same geographic area – from Mt

Druitt to the Hills to Parramatta and Auburn.

Good things followed in coordinating care and hospitals and community

practitioners learning to work together – for the good of the patient.

The document that evaluates the Medicare Locals concedes the

value of a one-on-one relationship but envisions larger organisations combining

the roles of smaller Medicare Locals.

What a pity. We know from past experience that the size of the NSW

health districts is just about optimal – make them bigger and they are a

managerial nightmare; make them smaller and you lose economy of scale. Each has a degree of local identity and that

identity is reflected in the Medicare Locals that serve the community especially

when the overlap is complete.

If the federal minister wishes to experiment with how to

meet the needs of the patient with chronic problems, why not leave NSW as it is

and try out different models in other states such as Victoria that has no fewer

than 90 hospital networks. Or

Queensland. He has encouraged private insurers

to experiment so why not his own ministry?

Tearing up the crop before it has had a chance to bear fruit

is expensive and wasteful. Even more so

with Medicare Locals. Of course many of

them can benefit from more energetic and focussed management, but there is no

monopoly on that. Let the plants grow. We’ll find out soon enough whether the NSW

model – one Medicare Local per hospital network – is the best way to go or

whether we have been trumped by the Victorians again.

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

THE FUTURE OF MEDICARE AND MEDICARE LOCALS

The

Conversation Conference

August 13th

2014

Recently-announced

proposed budget changes bear heavily on the future of Medicare and Medicare

Locals (MLs).

The

element in the budget that I wish to concentrate upon today is what’s happening

with the 61 Medicare Locals. I

have been asked to address three questions:

- The argument for ML reform - what has and hasn’t worked and what changes are needed?

- Will the reform of MLs work or will abolition be the only answer?

- What do we see internationally that could be applied within Australia to alleviate the problems with MLs?

MLs

have been reviewed both with regard to their function by John Horvath and

specifically with regard to financial management by Deloitte.

As

one might predict, the financial management of these entities was found to be immature

and often below par. As well, much diversity of competence and performance was

found in function among the MLs. General practitioners complained about being

excluded from MLs. Some feared

that they will take over their work.

In

any case the reviews proposed abolishing MLs and replacing them with Primary

Health Networks – PHNs – that have rather similar functions. Although the reviews proposed there

should be fewer PHNs than MLs, it emphasised the value of having MLs and Local

Health Districts – LHDs – or Local Hospital Networks – LHNs – relate closely to

one another. Contiguity was seen

as a virtue. How this will happen

is not clear. In NSW we have at

present 17 MLs and 17 LHDs. As John Horvath

observed in his review “to be effective, boundary alignment with Local Hospital

Networks (LHNs) is critical for engagement” but of course this will not be

possible at the PHN level unless there are more, not fewer, PHNs than there

were MLs.

Perhaps to overcome the mismatch

between PHN and LHNs, each PHN will have a board, informed by a Clinical

Council and a Community Committee for each LHN. These committees will oversee the functions that MLs provide

at present though it is clear that PHNs will not have a service role other than

exceptionally. The Clinical

Council is intended to give strong voice to general practitioners who

reportedly have felt excluded from many MLs.

A transition to PHNs may not involve

much change providing they remain the same size as the MLs. In Victoria where there are 90 or so

LHNs, things are not clear. In any case funding to MLs will cease next year. As John Horvath says in his report, “The role of the PHN is to work with

general practitioners, private specialists, LHNs/LHDs, private hospitals, aged

care facilities, Indigenous health services, NGOs and other providers to establish

clinical pathways of care that arise from the needs of patients (not

organisations) that will necessarily cross over sectors to improve patient

outcomes.”

The

argument for a name change is quite acceptable. ML is confusing.

The argument for abolition and then reconstruction rather than managing

the process of development of laggard MLs and learning from the ones that are

going well is less obvious. There

is no contestable policy visible, just a budget statement.

What

has worked? In western Sydney the

Western Sydney Local Health District (LHD) whose board I chair has worked with

the ML on six projects and has another important one under way. The ML does not

itself provide the service.

Rather, it coordinates and manages the players.

Indeed,

the function that the ML has proved most useful in managing in partnership with

the LHD is the increasing load of people with multiple serious and continuing

illnesses has been to link their care between hospital and community.

Our

district encompasses a population of nearly one million people, 40% of whom

were born overseas. We include

Parramatta, Auburn, and Westmead, Blacktown and Mt Druitt and all places in

between. We have our share of

older people and those living with economic disadvantage. There are three major hospitals – Blacktown

Mt Druitt – BMDH – Auburn and Westmead (WH), WH being the largest and BMDH

being redeveloped to become a major tertiary centre. Lots of hospital admissions are of people in crisis with

their chronic illnesses.

With

special sponsorship from NSW Health we are currently constructing integrated

care programs for people with a chronic health problem – heart failure, chronic

emphysema or diabetes. We are

doing this in partnership with our ML.

We are devising ways to centre care on the patient by brining into

formal relationship general practice, community health services, hospital

out-patient and community specialist acre and hospital inpatient services.

This

is aided by limited use of electronic records. It depends on good will and negotiation. It also depends on formal affiliations

between the ML and LHD because our sources of funding are different.

These

projects do not account for all that the ML does. For example it has also helped organise out of hours general

practice services in western Sydney and has partnered several prevention

programs. It is active as a provider of continuing education for general

practitioners and those in training.

Is abolition of the MLs essential?

There

has been no recent suggestion to reform MLs, just abolish them. Any restructuring in the health service

comes at a huge cost and serious disruption and that should be factored into

the argument for it.

I

am not as familiar with all aspects of the performance of MLs as the review

committees, but I am surprised that the proposal for abolition and then construction

of a group of organisations of roughly the same function was not available for

contest before it became an edict in the budget. I personally don’t think that the function of the MLs

warranted wholesale abolition. They were young and we had hardly a chance to

establish them. That is my point of view.

I could be wrong, of course.

But

the move to PHNs will be expensive and now we have private health insurers

wishing to contract with the federal government to provide PHN services. How this will serve public patients is

unclear. It is true that in the US

managed care transacted by private insurers has often achieved good outcomes

for integrated service delivery. But I cannot see how that could be provided in

Australia with its divided financial arrangements between states and

commonwealth, public and private patients.

So,

to western Sydney. Our district

encompasses a population of nearly one million people, 40% of whom were born

overseas. We include Parramatta,

Auburn, and Westmead, Blacktown and Mt Druitt and all places in between. We have our share of older people and

those living with economic disadvantage.

There are three major hospitals – BMD, Auburn and Westmead, WH being the

largest and BMDH being redeveloped to become a major tertiary centre. Lots of hospital admissions are of

people in crisis with their chronic illness. Before the ML there were active Divisions of General

Practice.

With

special sponsorship from NSW Health we are currently constructing integrated

care programs for people with a chronic health problem – heart failure, chronic

emphysema or diabetes. We are

doing this in partnership with our ML.

We are devising ways to centre care on the patient by brining into

formal relationship general practice, community health services, hospital out-patient

and community specialist

acre and hospital inpatient services.

This

is aided by limited use of electronic records. It depends on good will and negotiation. It also depends on formal affiliations

between the ML and LHD because our sources of funding are different. The features of this relationship

that have meant it is a success so far as it has developed that I can identify

include:

1. Managerial commitment and

compatible, mature personalities of the executives of both LHD and ML – both

share a belief that collaboration is feasible and desirable and a common goal of

contributing to the health of the district.

2. Overlapping geography.

This is important in preventing dual loyalties and administrative confusion.

There is no space for playing one master LHD or ML off against another.

Although successes have been achieved in some MLs where there are more

than one per LHD, reports of conflicts and sub-optimal performance are

common. We lobbied hard to have

the ML boundaries set to be the same as those of the LHD and have never

regretted it.

3. A common foe – the rising tide of chronic

illness.

Has this arrangement been optimal?

When it comes to integrated care the answer is no, because factors we know to

be critical in the achievement of integrated care are missing. But whether this is

ground enough for abolition – especially when the proposed replacement does

not, it seems to me, promise more that would enable truly integrated care to be

provided – is extremely thin.

International

models of relevance to MLs and PHNs.

If we take the fundamental task of

MLs or PHNs to be to integrate care for patients with chronic illnesses, then

we should look at overseas models.

Where integrated care works to reduce inappropriate use of hospitals

there is one payer as at Kaiser Permanente’s managed care for six million

Californians, and many of the McKinsey-supported projects in the US and the UK.

Complete electronic data systems are used to assess clinical performance and

health outcomes, guidelines and a keen interest is expressed in professional

standards for all practitioners, with rewards and sanctions for achievement or

non-compliance. The Veterans Affairs services in Australia bear close scrutiny

as a model in this regard. Pull

any of these pieces out of the integrated care structure and the whole thing

collapses. I know of no examples

of successful

integrated care that have been unmanaged.

We have none of these necessary

arrangements. These qualities of

successful integrated care are not within the power of general practice or a ML

or PHN to achieve whether embedded in a Commonwealth-funded arrangement or a

private insurance set-up given the way Australia funds health care though

separate silos. The initiatives

needed to change this belong with the major state and federal health

bureaucracies.

It is true that growing interest has been expressed by

private health insurers in the PHNs and where they might play a role. For example, Medibank and the WA and

Victorian governments have proposed a trial of intensive care coordination 3000

patients with complex and chronic health problems. 2000 of the patients would

be covered by Medicare and 1000 would in addition be privately insured. Community nurses would ensure all

patients are seen by their general practitioner within seven days of hospital

discharge. The interventions

proposed have elements found in most efforts to integrate care and are not

dissimilar to those found partially in many MLs. It is not clear whether the

proposals can extent to what is successful in Australia through the VA or in

the US through managed care.

So we have the foundations through

the LHD-ML liaison to provide more appropriate care for people with chronic

illnesses but no superstructure.

To drive towards optimality requires a common funding stream, tighter

management of the process and a set of quality performance goals that carry

incentives and sanctions.

These features are recurrent in the

successful models of integrated care with which McKinsey and Co, a consultancy,

have established in the US, England and Europe. They are similar to what the King’s Fund, a health service

think tank, in London also articulate, though in the NHS integrated care has

not worked as well as hoped. Tough,

but if you want it to work, observe what the ingredients are where it does

work.

The

way forward

Integrated

care is a necessary revision to the current model of disjointed care because

chronic illness is coming to dominate our health care agenda and this cannot be

done with optimal success when components of care are disconnected.

In

moving to PHNs to replace Medicare Locals we can expect a year or more of

disruption due to transitions and it remains to be seen what management

assistance will be provided to the agencies, presumably including private

insurers and existing successful MLs and maybe even LHDs/LHNs that contest to

provide the services of a PHN.

The

positive thing is that the need for integration is clearly recognised as is the

role of the general practitioner.

These are good omens. I do

not know what process the federal government proposes to use to implement its

approach to PHNs – we can only wait and see. This is not an era in our political history where policy –

either its formation or action that might be based on it – is obvious or

strong. But we can hope that gains

made by many fledgling MLs will not be lost.

A

call to action in the July 26 edition of the Lancet is especially apposite. “Primary care needs to be reshaped to truly function as the

most important pillar for people-centred health and well-being in the 21st

century. Primary care leadership needs to wake up and start a revolution.”

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Is an annual GP fee the answer to paying for healthcare?

The uproar over the proposed $7 co-payment for bulk-billed

general practice visits and pathology services raises questions about how we

pay for healthcare more generally.

But serious discussion is urgently needed in regard to the

billions that comprise the cake, rather than the thin icing of the new impost.

While I do it frequently, in my heart I know that there is

little point in lamenting that Australia does not have a unified health

financing system. It simply doesn't.

With the UK's NHS and managed care systems in the US such as

Kaiser Permanente, the entire health budget is managed by a single health

authority that can move money to where it is most effectively employed:

hospital or community, prevention or care, private or public.

Instead, we in Australia have these compartments that each have

their own lives to live, more or less independently. While that's not quite

true, it is close enough.

Given the improbability of Australia shifting within the

foreseeable future to a unified system of healthcare financing, we need to find

small, doable things that achieve efficiencies (which, when defined properly

mean effectiveness gains as well) where we can act.

A decade ago, I heard senior health service manager Dr Katherine

McGrath, now consultant at KM Health Consulting Services, suggest that, given

the rising tide of chronic illnesses that require continuing community-based

care, it would be wise to consider a better way of funding services for these

patients in general practice.

She suggested that an annual fee could be struck that would

cover all the services provided by a GP.

Average fees are exactly that -- patients may require more or

less service than the fee would cover but the end result should be even.

Of course, payment on this basis could be gamed, at least in

theory, but there is hardly anything unique about that.

More positively, an annual fee might help those GPs who wish to

develop and implement a preventive plan with their patients experiencing

serious and continuing problems to do so.

Such a system could give more clinical freedom for the GP.

Dr McGrath made a second point: episodic, acute care is

demonstrably well-managed within a fee-for-service system.

Occasional use of general practice would not need a system of

payment based on repeated visits. Immunisation, common infections, even minor

psychological upsets do not need continuing care.

"An

annual fee might help those GPs who wish to develop and implement a preventive

plan with their patients experiencing serious and continuing problems to do

so."

The fee-for-service element of Medicare would remain unchanged.

This hybrid arrangement may be politically workable. A change to

annual fee-for-service for chronically ill patients would need careful scrutiny

to ensure that unforeseen side effects don't mean that it is more trouble than

it is worth.

Such a proposal was advanced three years ago for the management

of patients with diabetes in Australia and the results of pilot testing have

not yet appeared.

The development of this method of payment would need careful

handling and would be unlikely to succeed if imposed from above.

But it might enable the development of different ways of caring

for these people, based more on their needs than now, with flexible

arrangements about how they could be seen and when.

For example, a special channel for patients with chronic

problems might be opened in a general practice where they simply turn up if

they need help or reassurance.

It is possible that practice nurses and others could play an

expanded role in their care. Recent US studies on the medical home -- a form of

patient-centred general practice -- have been encouraging.

The debate about how much a patient pays at the time of

receiving care vs how much they pay through their taxes when they are well will

not solve our current set of healthcare financing challenges.

The current administration of Medicare is already dauntingly

complex and the co-payment will add to that complexity.

We need to test new ways of paying for care in the community for

patients with serious and continuing illness.

These forms of payment will serve patients and the profession

best if they stimulate improved ways of providing care in continuity, new ways that

come from imaginative thinking by the doctors who provide this care.

Their

leadership is essential.

Professor Leeder is a member of the Menzies Centre for Health Policy at the University of Sydney, chair of the Western Sydney Local Health District Board and editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal of Australia.

Professor Leeder is a member of the Menzies Centre for Health Policy at the University of Sydney, chair of the Western Sydney Local Health District Board and editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal of Australia.

Published Australian Doctor, 23 July 2014.

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

MJA CENTENARY – OPENING ADDRESS

Stephen R.

Leeder

Editor-in-Chief

July 4th 2014

The University of Sydney Great Hall

Welcome

This is a grand day and one to be

savoured. I am delighted to

welcome you to the University of Sydney for this centenary celebration. I thank

deputy vice-chancellor Professor Shane Houston for his warm and dignified

welcome on behalf of the original custodians of this land, the Gadigal people

of the Eora nation.

I also welcome Associate

Professor Brian Owler, national president of the AMA, his predescessor Dr Steve

Hambleton, Ms Anne Trimmer, secretary-general of the AMA and Ms Jae Redden,

general manager of AMPCo. I also want to acknowledge my editorial, journalist and production colleagues from the Journal and from MJAInSight, and our support staff in commercial development, human

resources, finance, business development and information technology who work

together to make the Journal a

success.

I acknowledge members of our

Editorial Advisory Committee who give us strong and careful guidance and to our

many colleagues who send material to us, our reviewers and our commercial

sponsors. I also thank our

splendid array of distinguished presenters.

I am immensely grateful to Dr

Richard Smith, a former editor of the British

Medical Journal who has

demonstrated in his subsequent global health career that there really is life

after being an editor, who comes as our master of ceremonies for today’s

symposium and this evening’s dinner.

Richard will shortly describe to us the order of proceedings.

The organisation of today has

involved a joint effort by many members of our MJA team, especially Zane Colling and Mel Livingstone. Denise

Broeren of Think Business Events, Laissez-faire Catering and DJW Projects for

AV also deserve great appreciation.

And finally I want to acknowledge and thank our sponsors who have been

generous in their support.

Origins

I want first to speak briefly about

our origins as a journal then mention several high impact papers that the Journal has published, then consider

what one hundred years of Journal

publication means beyond the effects

of individual papers. I will

conclude with a glimpse of where I believe the Journal is headed.

When I was approached about the

editorship of the Journal 18 months

ago, Steve Hambleton, who was then national president of the AMA and chair of

the board of the publishing company, talked with me about an event to mark the one hundredth birthday

of the Journal.

I have wondered whether in

approaching me Steve had in mind that I was of an age where I had a natural

empathy for older things. Indeed I can boast of having read and contributed to

the MJA for half its one hundred

years – admittedly the latter half – so it’s true that I know a bit about

it.

The Medical Journal of Australia emerged in 1914. We can thank Dr

Cumpston, the father of public health in Australia, whose achievements are

celebrated in a wonderful book by Milton Lewis, the editor of our centenary

supplement, for providing a short history of the ten principal forerunners of

the MJA between 1846 and 1914. These

were attempts to foster communication among the medical profession in the

colonies. The Australian Medical Journal,

the MJA’s immediate forerunner,

operated impressively from 1856 to 1914.

Cumpston notes that in the

absence of a medical Journal, medicos

had to resort to newspapers to publish their views. He refers to an article

published 110 years before the first issue of the MJA in the October 14, 1804 edition of, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser Australia’s first

newspaper.

The article was by one Dr Thomas

Jamison and was the first on a medical subject published in the public press of

Australia. Dr Jamison had a lot to

say about smallpox vaccination in Australia. He admonished parents who mistook chickenpox for

smallpox. “There is no smallpox here”,

he said, “save for few cases spread among the natives by French ships anchored

in Botany Bay”.

But he warned that it could come

and ‘carry off nine-tenths of those affected’. “Look at the Cape of Good Hope”,

he said, “on the same latitude as Australia, where smallpox is rife.” He urged parents to have their children

vaccinated because “the preventive qualities of the Cow Pock are

incontrovertibly established; [and] it is attended by no sort of danger or

external blemish.”

”Therefore,” he thundered, (quote)

“should parents delay to embrace the salutary benefit now tendered gratuitously

and the vaccine be lost, the most distressing reprehensibility may accrue to them

for their remissness in the preservation of their offspring, whose destruction

heretofore may be reasonably apprehended to ensue from the smallpox should it

ever visit this colony in a natural state.” This is a style cultivated by

relative few contributors to the MJA

today. Jamison’s letter is able to

be viewed in the University of Sydney Fisher Library archives.

Editors

I stand

before you, the 16th regeneration not of Dr Who but of the editor of

the Medical Journal of Australia. The

first three Doctors occupied 63 years of editorship. and passed the torch to the

13 of us who have followed. But the

13 who followed, rather like the Australian cricket team often is in India,

have not lasted long save for Martyn Van Der Weyden, who was a wag in the tail

of the team, so to speak, for 15 years.

My immediate predescessor Annette Katelaris was editor for eleven

months. Her contribution was both controversial and transformative.

High-impact publications

How

should we judge the effect of the Journal?

The social media savvy amongst us will know that clout is measured by clicks. For

example MJA.com.au averages 400,000 clicks

per month and nearly 200,000 from clickers who click and stick to read.

But citations remain the royal currency in Journals. In our centenary issue of the MJA, Dr Diana McKay, one of our medical editors, used the Web of

Science citation analysis tool to examine popularity of articles published in

the MJA from 1949 to 2014 by

citation.

Safety

First

ranked is the 1995 Quality in Australian

Health Care Study by Ross Wilson, Bill Runciman, Bob Gibberd, Bernie Towler

and John Hamilton, a reprint of which you will find in your symposium satchel. I

am delighted that Bill and John are with us today. I have heard them both lecturing recently and twenty years

has only improved their vintage.

Their

paper demonstrated the shocking potential and moral imperative to improve the

quality and safety of hospital care. It prompted the Australian Government to form

the Australian Commission on Safety and

Quality in Health Care launched in 2006. The Commission’s recommendations

were written into legislation with the National

Health Reform Act 2011. The paper also ignited international interest with

replications of the study internationally, including by the WHO in developing

countries.

Ulcers

Ranked

2nd and 3rd are two papers by Barry Marshall, a Nobel

Prize-winner, on pyloric Campylobacter.

In our

Centenary issue, Barry Marshall reflects on his work in an article titled “What

does H pylori taste like?” He

describes “the deliberate self-administration of Helicobacter pylori and the observation that it caused an acute

upper gastrointestinal illness with vomiting, halitosis and an underlying

achlorhydria.”

He remembers

the audacity of my predecessor as editor, Alistair Brass, and being (quote) “impressed

by how far the MJA Editor was

‘sticking his neck out’ in allowing me to publish a hypothesis as to the cause

of peptic ulcer”. Both of them lauded and lamented the beating the paper took

from reviewers to get it into its final published form.

Lithium

The next most popular paper is

probably the most widely recognised, described once as a “jewel in the crown”

of the MJA. Professor John Cade’s

article “Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement”, published in 1949,

held the Journal’s most-cited paper position

for decades. To this day, lithium retains “its royal status in clinical

practice guidelines”. Gin Mahli, a Sydney psychiatrist, writes. “Lithium is

arguably the best agent for the most critical phase of bipolar disorder, long

term prophylaxis and as such it is the only true mood stabiliser. Put bluntly,

it works”

These papers and many more have

had good and immediate effects. Some

take a while. Recently I read a

paper written 60 years ago on drink-driving. The writer, Dr F S Hansman who had an interest in the

biochemistry of alcohol, had asked doctor-colleagues at what level of alcohol

consumption did they consider their driving to be impaired. “After two whiskies or less”, 90% of

them said. Dr Hansman found that

this corresponded to a blood alcohol of 0.04. It took 23 years before random breath testings using a

standard of 0.05 became law.

Going deep, beyond the published papers

Beside recording scientific

advances for immediate or deferred application, the MJA serves another splendid function. The one hundred years of the Journal comprise a superb record or memory of medical achievement

and of the people who made it happen.

Hilton Als, an American novelist,

theatre critic and staff writer at The

New Yorker, gave a commencement address at Columbia University in NYC on

May 21 this year to the graduating class of the School of the Arts. Als called

his address Ghosts in Sunlight. You

will find it in the July 10 issue of the New York Review of Books.

Als’ address takes its title from

an essay by Truman Capote published when he was 43. Capote’s essay, Als told the graduating students, describes

Capote’s experience on the set of the first film adaptation of his 1966

best-seller In Cold Blood. This was a

non-fiction novel about the 1959 murders of Herbert Clutter, a farmer from Holcomb, Kansas, his

wife, and two of their four children and the

murderers. Some of you may have

seen the recent version of the film.

Ghosts in sunlight

Capote found his encounter with actors

who were developing and forcefully portraying real characters from his book –

victims and murderers – deeply disturbing. Capote described how he felt he was watching ‘ghosts in

sunlight,’ as the characters he had written about had come back to life.

I doubt that we will find

anything quite as exciting as In Cold

Blood when we thumb through the archives of the Journal, but we can easily become absorbed reading the stories of

the science and clinical practice and health policy of past years and as the

characters come back to life in our imagination.

It can be disconcerting to

revisit those memories, to revive the ghosts in the sunlight of our moment. It can be disconcerting to read reviews

of the science of ailments such as obesity that have hardly changed in fifty

years and of other conditions, such as heart attack, that have changed

radically. Stories of sepsis in

the pre-antibiotic era are frightening.

Yet understanding what progress we have made or failed to make can

change us, change our views, and stimulate our imagination.

I hesitate to answer questions

from well-intentioned inquirers when they ask which papers in the Journal changed medical practice. It is a perfectly proper question, and I

have referred already to a list in the centenary issue of the Journal of the ten most cited papers.

But above and beyond those papers

with their tangible achievements and changes to how we do things, though, is the

marvellous artistic process, the alchemy, by which the stories and memories and

encounters contained in those hundreds of thousands of pages came about. This is the story behind the story, if

you will.

The hard work of science

Scientific achievement as

recorded in the MJA is always hard

won. I spent 1963 working with John Pollard on a neuroscience research project

at this university in the pharmacology department as part of a BSc(Med). We

were in search of the elusive transmitter substance between the optic nerve and

the lateral geniculate body in cats.

We did not find it. Indeed when

we presented our finding of a stimulant in extracts of sheep optic nerves that

made smooth muscles twitch and which we could not characterise and wondered if

this was the transmitter it didn’t work.

When we presented our findings at

a neuroscience conference, Sir John Eccles chaired our session and told the

audience that a colleague had found a similar substance in extracts from his

socks after a brisk game of tennis.

In returning to complete my

medical degree I recall opening Cecil’s textbook of medicine and thinking

“Every line in this book represents a research worker’s life.” The ghosts were clear in the

sunlight.

In the commencement address I

have been referring to, Hilton Als quotes Caribbean-born writer Jean Rhys who

said that: “she considered her writing to be the tiniest stream. But without

those streams, there would be no ocean, and if there is no ocean there is no

shore, and if there is no shore there is no place for our ghosts to gather in

the sunlight, those artistic forebears who wave us back to dry land when a

project seems beyond us and we lose our way, which is at least half the time.”

Neils deGrasse Tyson,

an astrophysicist and science

communicator at the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural

History in NYC, in his TV series Cosmos

puts it another way: “Science is a

cooperative enterprise, spanning the generations. It's the passing of a torch

from teacher, to student, to teacher; a community of minds reaching back to

antiquity and forward to the stars.” It is the background culture and society

of medicine and medical research that you will find in the MJA that can be as informative and stimulating as individual papers

and articles.

Lessons from the ghosts

The ghosts of the practitioners

and scientists can change us, too, even now, even when we know that past

proposals were often wrong, that many of the lines of inquiry led nowhere

really. They can help us toward

humility; they can help us see how we, too, like the authors of the pages that

we turn, are creatures of our time.

They can make us tolerant of the

false starts, of the well intentioned failures, even of the pomposity of our

colleagues. (‘What’s good for

doctors’, opined the first editorial in the MJA,

‘is good for the community!’ Ahem!)

Ghosts can also frighten us: Capote writes about having to take a bottle

of scotch to bed to obliterate the ghosts of the characters of his book from

his consciousness.

When all of the issues from 1914

the MJA are digitised, as we plan them

to be when we have raised the $70K for that purpose (hint, hint), exploration

of the past and encounters with its ghosts in the sunlight will be a possibility

for all, anytime, anywhere.

Glimpsing the future

Today we celebrate a unique

record of medical memory in Australia that stretches back 100 years. This can be a day to renew our quest

for sounder medicine, for safer and better patient care, for new insights into

preventive possibilities and indeed to recognise and manage our own humanity

and frailty and proneness to error with gentle acceptance. The ghostly values can warm and correct

us and set our hearts racing.

The MJA has a bright future if we maintain our deep respect for

science, for imagination and humane concern for our patients, the profession, and

society and indeed for everyone in the organisation that contributes to the Journal. As we look to possible futures of the Medical Journal of Australia, we need to be open to the unbidden,

the unplanned, and the serendipitous that is never completely captured in a

strategic plan.

We are in the middle of the most

exciting explosion of knowledge in human history, with multiple media to

communicate and sift it. These dynamics will affect the form and style of the Journal and even its ethics. The format

of the Journal will need to become

more attuned to contemporary ways of communicating, the content more flexibly

responsive to the needs of our diverse readership through electronic tailoring

and streaming of content to them where and when they need it. Already we have a substantial presence

in the social media and this will grow.

To remain a trusted instrument of

record, where contemporary medical knowledge and reflection is written

carefully and history is recorded, that

will require all our skill and imagination about new and efficient ways of

communicating through multiple media.

That is what we at the Journal are committed to doing and we

thank all of you for your continuing support as we move into our next century.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)